Mysteries in Mudstone

By Melissa Bowerman, Assistant Curator, Geology

May 2, 2020

Humans have a natural ability to find patterns in randomness. It’s a skill that comes in handy if you are a geologist or palaeontologist trying to answer scientific unknown. Fossils are can be identified when they resemble familiar patterns, but what happens when scientists encounter a bizarre new form?

In 2013 a group of geologists in northwestern Alaska made a discovery of strange twisted features up to a metre long in the rocks they were mapping. These forms had helical and spherical shapes and didn’t resemble any known fossils.

The geologists photographed their discovery and took samples, which came to RAM for investigation. Our initial guesses covered a wide range of options: was it fossilized shark poop? Methane escape features? Helical burrows? The specimens puzzled us.

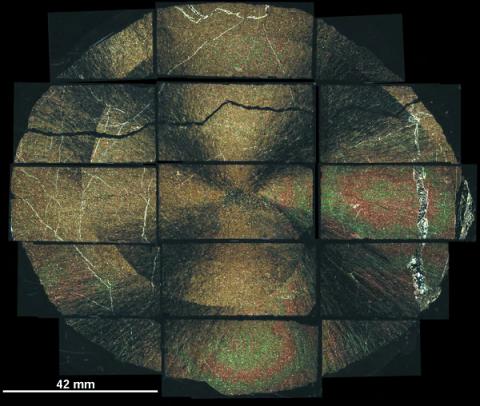

We partnered with researchers at the University of Alberta to study these features, and decipher how they formed. To do this, we examined the internal structure of these forms using thin sections, a process that makes slices of rock thinner than the width of a human hair. Under a microscope, we pass light through the thin sections to identify minerals and structures present. This revealed beautiful radiating crystal of the mineral calcite.

|

Image

|

Image

|

Photos courtesy: Andrew Locock et al

With no evidence for fossils or other biological activity, we can officially call these features concretions.

Concretions are formed where sediment is naturally cemented in a particular area, making that patch more resistant to erosion than the surrounding rock. Concretions are a fairly common geological feature found in many places, including Alberta. They are notorious for their bizarre shapes.

The most well-known concretion at the museum is the “holey concretion” that has been on display since the museum opened in 1967. This concretion formed in a similar way: minerals grew in soft sediment and expanded from a single point to create a sphere.

|

Image

|

Image

|

This is a perfect scenario, but if the crystals deviate from that plan, they can create the helical shapes like the ones found in Alaska.

What this study discovered is that not all “perfect” shapes have a biological origin story. Minerals can create beautiful forms that can easily be mistaken for fossils.