The Lossie Lane Quilt: A Testimony of Friendship Between Two Black Pioneer Settlers

January 23, 2024 (First published March 22, 2017)

by Lucie Heins, Assistant Curator, Daily Life and Leisure

A number of quilts made by early Black pioneers have been donated to the Royal Alberta Museum. One such quilt is the Lossie Lane quilt. Through a series of conversations with her granddaughter Christine Beaver, I am able to share the life of another Black pioneer and quiltmaker.

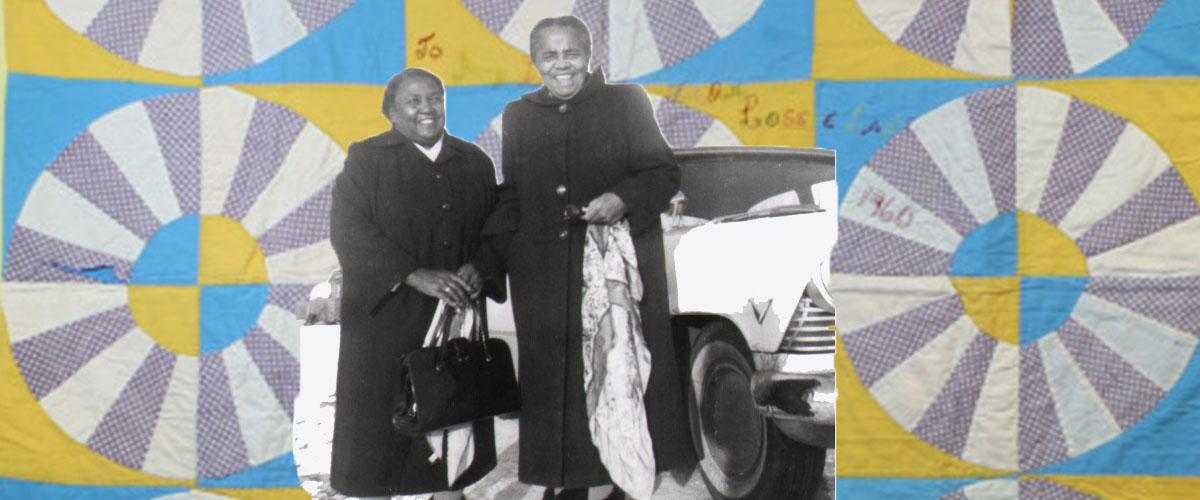

Lossie (Barksdale) Lane made a quilt for her dear friend Ivy Beaver. Although it was their experiences as early Black pioneers to Canada that solidified their friendship, they did not actually meet until their adult children married each other on April 8, 1950. The union of Ollie Lenora Lane and James Willis Beaver, Christine’s parents, planted the seed that blossomed into a lifelong friendship.

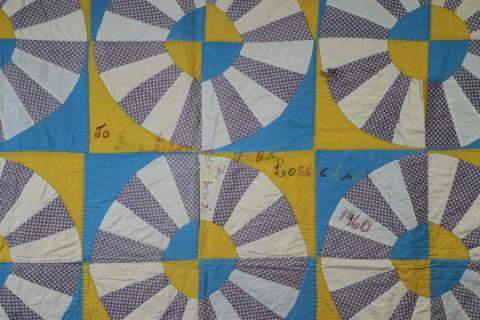

Lossie and Ivy lived different lives in different communities but both had moved far away from what had been their home in the United States to a new home in Canada. Lossie’s Friendship Quilt is a testimony of that friendship as noted in the inscription on the quilt: "To Ivy Beaver Remember Me From Lossie Lane 1960"

The Lane family came from Oklahoma, USA. Christine’s maternal great-grandfather Julius Caesar Lane (age 59) and great-grandmother Emma (Bruce) Lane (age 42) had both been born into slavery. They made their way to Maidstone, Saskatchewan in 1909, two years after Oklahoma and the Indian Territories merged to form the State of Oklahoma. Within a short period of time new segregation laws were introduced, making life difficult for the African American community. Many began to look to Canada for refuge; free homesteads were available in Western Canada. In the article “The Shiloh People: Maidstone, SK” author Leander K. Lane writes that a “Canadian border entry record show that at least seventy-five individuals representing 12 different families arrived at Emerson, Manitoba in the spring of 1910. They all stated their destination as Maidstone Saskatchewan.” In 1912 Julius and Emma Leotis’ son Leander Lane Sr., his wife Lossie and their eldest son, Leotis, travelled to Maidstone to join them. They came at a time when Alberta and Saskatchewan sentiments against African American immigration encouraged the Government of Canada Order in Council to bar such immigration. Although the law was never passed, it would appear that Leander and Lossie almost never made it into Canada. The family lore suggests that Lossie Lane had said, “They didn’t have to be so mean to us” in reference to the border officials of the day. Despite encountering racism, many hardships and cold winters, the Lane family were able to find contentment in their new home.

The Beaver family also came from Oklahoma. Christine’s paternal great-grandfather James Moses Beaver (age 45), great-grandmother Hattie Miller (age 40) and their two sons James “Edward” (age 17) and Walker Miller (age 13) were the only Beavers to cross the Canadian border at Emerson, MB. In 1911, they further travelled to the city of Strathcona by train. In May 1912 when their household effects and basic farming tools arrived in Edmonton on a freight train, the Beavers made the three-day, 138-km journey to the smallest Black pioneer settlement of Campsie, 16 km west of Barrhead, AB. According to Christine’s granddad, Walker, his mother rode in a horse-drawn buggy while he, his brother and father walked and led a team of oxen pulling a cart full of their possessions. On their way to their homestead in Campsie they had to unhitch the oxen several times to pull the buggy through the mud holes, the muskeg and the underbrush. Walker Beaver said the mosquitos were fierce.

In March 1920 Walker Beaver married Ivy Belle Bowen in Amber Valley, AB. Ivy was born in Evergreen, Alabama and eventually moved with her family to Amber Valley. Once married, she moved to her husband Walker’s homestead in Campsie where they raised their family. Christine’s father, James Willis, his brother and two sisters attended the Benton School of District #3319, officially recorded by the government of Alberta as the only designated “segregated” or “blacks only” school district in Alberta. Despite this designation, many parents of white students opted to send their children there because it was closer than the school for “whites.“

Life was never easy on the farm, but Ivy’s tenacious character coupled with her “waste not” attitude made her a formidable farmwoman. She raised chickens and turkeys, selling their eggs. She also planted enormous gardens. Ivy had a reputation for having one of the most beautiful flower gardens in the community. Her foundation plants included rose bushes, lilacs and apple trees creating a backdrop for the hundreds of seedlings she planted each spring. Every January the dining room table became a plant nursery. She started her seeds in tinned cans she’d saved all year just for this purpose.

After Lossie’s husband, Leander Lane Sr., died of prostate cancer in 1947, Lossie left Maidstone to live with her eldest daughter Rosie (Lane) Walker in Edmonton. Christine remembers that every summer her grandmother came to stay with her family on the farm in the community of Tiger Lily, eleven km northwest of Campsie. Christine’s father James Willis had moved from Campsie in the early 1940s to the second homestead registered to his grandfather James Moses. Lossie took residence on the top floor of the house. There she would spend six to eight hours a day, except for Sundays, hand-stitching quilts. According to Christine, her grandmother “pieced everything together by hand…She had the patience of Job”. By the end of the summer, Lossie would have completed a batch of brand new quilts. Christine remembers that “every quilt on the beds at home was made by my grandmother.”

It was during these summers that Christine learned to sew and make quilts. When Christine was six years old her Grannie Lane instructed her in the art of threading needles. She would thread five to 10 needles at a time and leave them within reach of her grandmother’s hands. Christine remembers her grandmother calling her in a booming voice, “Christmas!” as this was her nickname and “she would give me two squares to stitch together.” She sewed quickly so she could go out and play but Grannie Lane would take one look at her stitches and tell Christine to rip it out and start again. Christine says that to this day “if it doesn’t look right I rip it out.” Christine has become an accomplished quilter due to spending so much of her formative years with her grandmother.

Having experienced economic challenges, Lossie was always frugal and resourceful. She always used what was readily available to make her quilts. After a fire at the local variety store located on Hastings Street in Burnaby, B.C., Lossie rescued and cleaned smoke-damaged blue and yellow shirts, then took them apart and used them for the blocks, border, and backing of the friendship quilt (below). Although Christine is not sure where the other fabrics came from, it is likely to have been other scraps of clothing, flour sacks, and old curtains.

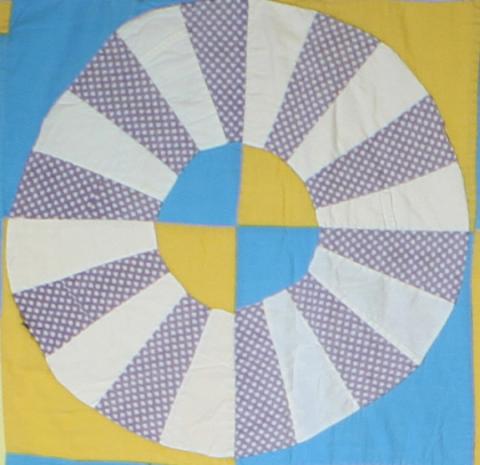

The pattern used for this quilt is called Wagon Wheel. It is not certain if Lossie specifically chose this pattern for Ivy or whether it was what she had on hand. According to Christine’s grandmother, this quilt pattern was once used to signal wagons heading north to Canada as part of the Underground Railroad. In a radio interview with NPR News Station in Washington D.C., professor of art history at Howard University Dr. Raymond Dabard talks about how quilts were embedded with coded messages using traditional American quilt patterns. One such message was “The Monkey Wrench turned the Wagon Wheel toward Canada on the Bear’s Paw trail to the Cross Roads”. The Monkey Wrench, the Wagon Wheel, the Bear’s Paw and the Crossroads are all quilt patterns. This code was imparted by Ozella Williams known as the quilt lady in Charleston, South Carolina to Dr. Raymond Dabard and Jacqueline Tobin, co-authors of the book Hidden in Plain View: The Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad. She was also the keeper of stories in the African Tradition. When a quilt with these patterns was put out to be aired, the hidden message was that wagons (Wagon Wheel) were headed north, to stay close to the mountains (Bear’s Paw) until you get to Cleveland, Ohio (Crossroads).

Christine also remembers her grandmother telling her that the colours used in the quilt would indicate whether you would be travelling in a box in the wagon or travelling under the wagon. According to Dr. Dabard, Ozella Williams also mentions the importance of colour in the quilts but did not share examples of how the colours were used. It must be noted that there has been some controversy on the topic of quilts and the role they played in the Underground Railroad. It is not surprising as there is little physical evidence since the making of these quilts was part of a covert operation. Only the stories passed down from generation to generation provide us with a glimpse of this practice. As more of these quilt stories surface, these overlapping oral histories much like the story passed down from Lossie to Christine in the late 1960s, will be hard to ignore.

The Lossie Lane quilt pattern reflects an earlier history of the Underground Railroad while the quilt itself embodies the friendship of two women, two friends, both early Black settlers, who left one home behind on their own terms to make their way to a new home on the Canadian prairies, surviving harsh winters and sometimes harsh words.

Join me next time as we discover Alberta’s history…one quilt at a time.