Lightning in a Bottle

By Julia Petrov, Curator of Daily Life and Leisure

July 31, 2021

In Alberta, we often say, “if you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes!” Although it’s true that all weather does, eventually, pass, it sometimes leaves a dramatic trace on our lives and landscapes.

July 31, 1987, saw one of these devastating weather events in the Edmonton Area. The “Black Friday” tornado ripped through the east side of the city, causing death and destruction. Many residents of the city witnessed this event, and often reminisce over photographs on anniversaries.

But how can a museum capture a weather event that is by its nature, fleeting? How can you collect objects, when the point of natural disasters is that they destroy property? Looking over our collections holdings, it would be hard to tell that Alberta was ever hit by disasters like the tornado at Pine Lake in 2000, or the Southern Alberta floods in 2013, or the Fort MacMurray wildfire in 2016. When materials are swept away, survivors salvage what they can, but often have to start from scratch.

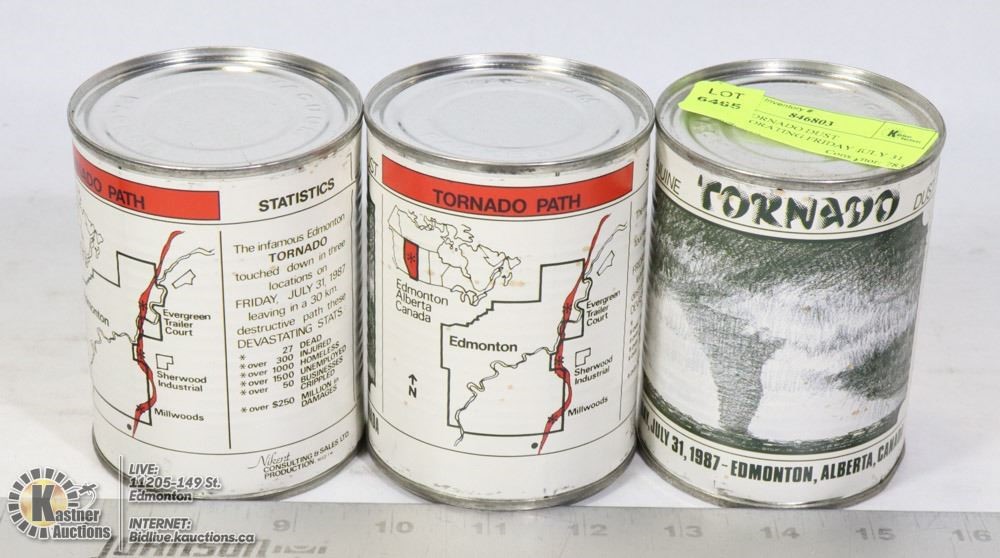

That’s why I was very intrigued to hear about a novelty souvenir item produced to commemorate the Black Friday tornado. Sold at auction on the anniversary of the event in 2020, aluminium cans purporting to contain genuine tornado dust were being resold on Kijiji earlier this year. These cans, created by a company called Nikent Consulting, had a map of the tornado’s path, stats about the effects, and were in mint condition.

These were clearly gimmicky items, like the cans of “fresh mountain air” you sometimes see in gift shops, but were one of the few ways we could document that such a thing ever happened, outside of archival sources like newspaper articles or photographs. I reached out to the seller, who agreed to allow us to add two to our collection.

Why two, you ask?

Generally, once objects are added to museum collections, we don’t alter them in any way. Exceptions can be made for safety (taking out the batteries from a vintage toy to avoid corrosion) or for conservation treatment. However, as a rule, we do not change the physical condition of any artifact in order to preserve it for the future.

If we only added one can to the collection, like Schrodinger’s Cat, we would never know whether the can actually contained any tornado dust, as we would not be able to open it after the fact. I am far too curious to let that happen! Unfortunately, any technology to view inside the can without opening it (such as Xray, or even MRI), would be both prohibitively expensive, nor would it show something as small as dust inside.

Armed with a can opener (an unexpected, but handy tool in my museum arsenal), I carefully unsealed one of the cans. My colleagues and I imagined that the cans were created by some enterprising Albertan who, as unflappable as the iconic Three Hills Lawnmower Man, was outside as the tornado winds whipped around him, gathering flying debris with a shop vac. Although shaking the sealed cans didn’t produce any sound, we were nonetheless hopeful that the original purchasers of these cans weren’t duped!

Before I reveal the result, I must confess to the limitations of the experiment. The museum does not have a “clean room”, and we do not have the kind of analytical equipment necessary to test air nor swab the inside of a can for residue (such as what you might see at security points in an airport). We had to rely on our human senses to know whether anything was inside.

When I peeled back the lid of the can, I am sorry to say that it was empty, with no sign of any tornado dust, genuine or otherwise.

Despite this disappointing result, we can nevertheless learn a lot from even an empty can. We can see how certain weather events leave a lasting trace on our collective memory, and how some enterprising Albertans have created commercial responses to these disasters.

That said, we are very interested in hearing from anyone who knows more about the creation of these cans. We also want to collect any tangible items relating to major natural disasters in Albertan history: do you have a fire, flood, hail, or wind-damaged item you salvaged? Something you wore as part of recovery efforts? The last thing you grabbed as you left your house for safety? Please get in touch so that we can tell the stories of these important weather events to future generations.