May 29, 2024

By Chihiro Iwamoto, Administrative Assistant

When Canada declared war on Japan in 1941, people of Japanese ancestry were met with intense discrimination. The Canadian government ordered the removal of Japanese Canadians from the West Coast of British Columbia in 1942, and within two months, approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians, about three-quarters of whom were born in Canada, were forced to leave their homes and their properties were confiscated.

Most male Japanese Canadians were sent to labour camps to work on road construction, while their families were sent to internment camps in interior British Columbia.

Around this time, Alberta's sugar beet industry struggled to secure labour due to the heavy, harsh, labour-intensive nature of sugar beet cultivation. A group of 560 Japanese families agreed to move to Southern Alberta by 1943, where they signed a labour contract to work in the sugar beet fields because it allowed the families to stay together. One of the communities they were relocated to was the small town of Picture Butte, about 27 km north of Lethbridge.

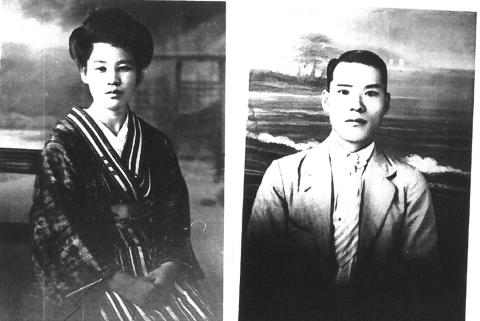

Nobuichi Takeyasu and his wife Shizuyo

Nobuichi Takeyasu and his wife, Shizuyo, had moved to Vancouver from Hiroshima-ken in 1920. They ran a tailor/dry cleaning shop and chiropractic office there. Nobuichi was trained as a carpenter in Japan, and he eventually went back to carpentry while living in Canada, mostly building fishing boards, until they were evacuated to Picture Butte with their children in 1942.

Southern Alberta was not exactly welcoming to these Japanese Canadians. Accommodation for Japanese workers was generally inadequate, especially in winter. The houses which were available had been originally built for use only in the summer, and some families had to live in barns or deserted schools.

In the first winter, almost half the families had to go on relief because they had not earned enough in summer. This was partly because the number of acres, which they cultivated was not properly adjusted to the assigned family’s size, and partly because the work was unfamiliar. During the winter, many of the men worked in canneries and lumber camps. The relief was terminated in May 1943 to encourage their economic independency.

Japanese Sugar Beet Workers in Southern Alberta, C. 1911

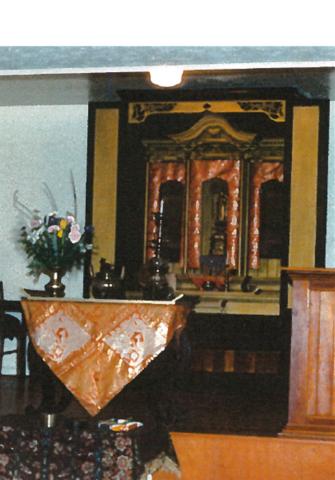

The displaced families were allowed very little time to pack their belongings before their relocation. As they settled into their new town, the families worked together to establish the Picture Butte Buddhist Temple. This temple was a makeshift affair, as the community was unable to import necessary materials from Japan. The altar was created from bits and pieces collected by relocated Japanese families and discards donated by the established Japanese communities of Southern Alberta. The shrine’s missing elements were hand crafted by Nobuichi Takeyasu.

Wooden shrine of Jyodo-shinsyu. The main portion of the shrine was too large to be brought with the families and was built in Picture Butte by Nobuichi Takeyasu.

Some Japanese immigrants adopted Christianity upon arrival. However, the majority of Japanese Canadians in Alberta were members of Jodo-Shinshu Buddhism. Several Buddhist temples in southern Alberta have served as social, religious, and cultural focal points for Japanese Canadians in the area, thereby fostering their ethnoreligious identity.

After the war, many displaced families moved elsewhere, but quite a few stayed in southern Alberta in part due to the well-established communities anchored by the temples. In some ways, the policy of forced relocation, albeit unintentionally, promoted Pure Land Buddhism in Canada.

Picture Butte Buddhist Temple. The Picture Butte Buddhist Temple was in service from 1942 until 1992.

RAM is honoured to care for a number of objects from these Buddhist temples, from other Japanese Canadians who moved to Southern Alberta, as well as carpentry tools from Nobuichi Takeyasu. Learn more about each of them below.

|

Image

|

Image

|

Gohonzon of Jyodo-shinsyu, Amida Nyorai. The Buddha of the Western Paradise, performs the gesture of teaching with both hands. In East Asia, these gestures signify Amida's welcoming descent from heaven (raigo) to greet the soul of a faithful devotee at death.

|

Image

|

Image

|

Japanese Buddhist prayer beads can have two names: either nenju (thought beads) or juzu (counting beads). In the Jodo Shinshu sect of Buddhism, prayer beads are used more for the ritual process than for counting the recitations of the nembutsu or Amida Buddha's name.

|

Image

|

Image

|

|

Image

|

Image

|

Two traditional Japanese handmade planes for shaping wood surface smoothly. This type of Japanese plane is known as "tachi-ba-kanna" or "standing-blade plane". The blade is straight and set at an angle of 90 degrees (to the sole) in the mouth of a rectangular-section hardwood body. The maker's mark in Japanese characters on the blade. 1900s-1950s. One plane has the initials "N. T" short for Nobuichi Takeyasu, embedded in the end of the tool.

|

Image

|

Image

|

Two worn bags believed to have been used by Nobuichi Takeyasu as a drop cloth and to carry tools . The first is printed with Japanese characters that translate to 'Osaka Mainichi Newspaper.' The second is a rice bag, from the company Nomura and Company in San Francisco, California.

Sources:

https://nikkeiculturalsociety.com/japanese-canadians-history/

Lethbridge and District Japanese Canadian Association History Book Committee, Nishiki: Nikkei Tapestry: A History of Southern Alberta Japanese Canadians (Lethbridge: Lethbridge and District Japanese Association, 2001)

Aya Fujiwara, “Japanese Canadian Internally Displaced Persons: Labour Relations and Ethno-Religious Identity in Southern Alberta, 1942-1953.” Labour / Travail 69 (Spring 2012): 63–89.

Aya Fujiwara, “Informal Internment: Japanese Canadian Farmers in Southern Alberta, 1941–1945,” in R, Hinther and J. Mochoruk, Civilian Internment in Canada: Histories and Legacies, University of Manitoba Press, 2020, 174-186.

British Columbia Security Commission Report, Alberta Sugar-Beet Project, July 9th, 1943