The Basket Tree (Part 2)

By Skye Haggerty, Former Indigenous Student Museum Intern

Originally published July 2019

For many Indigenous Peoples, the availability of birch and spruce trees made their bark and roots essential materials for the creation of every-day items such as baskets. Not only is this material extremely practical, it also provides a unique medium to showcase artistic talent.

Some of my favourite memories involve going into the bush with my grandmother to collect the papery birch bark for her crafts. In the winter, I’d get to chew on spruce gum while she collected roots from the muskeg in our backyard. Sometimes these trips came with tea and cold bologna sandwiches, sometimes not, but they always included a teaching or two about Grandmother Tree and her gifts to us.

In this two-part blog post, I’ll explore the importance of these materials, the process of harvesting them, and a few of the traditional crafts my grandmother taught me to make from them. Read part 1 here.

The Basket Tree

After harvesting the needed materials for a birch bark basket from the forest in my prior post, my grandmother and I set to making the baskets (and a few other items too).

The baskets created from this natural material can be used for anything ranging from berry-picking to water hauling (if sealed with a resin commonly called pitch) to being a decorative container for household knick-knacks. To create a birch-bark basket you’ll need a few more tools:

- A good pair of scissors

- A pencil or pen knife

- Construction paper

- Sinew or spruce root

- A needle

- A dowel for puncturing holes

- Clamps or paper clips

Now, you draw your pattern!

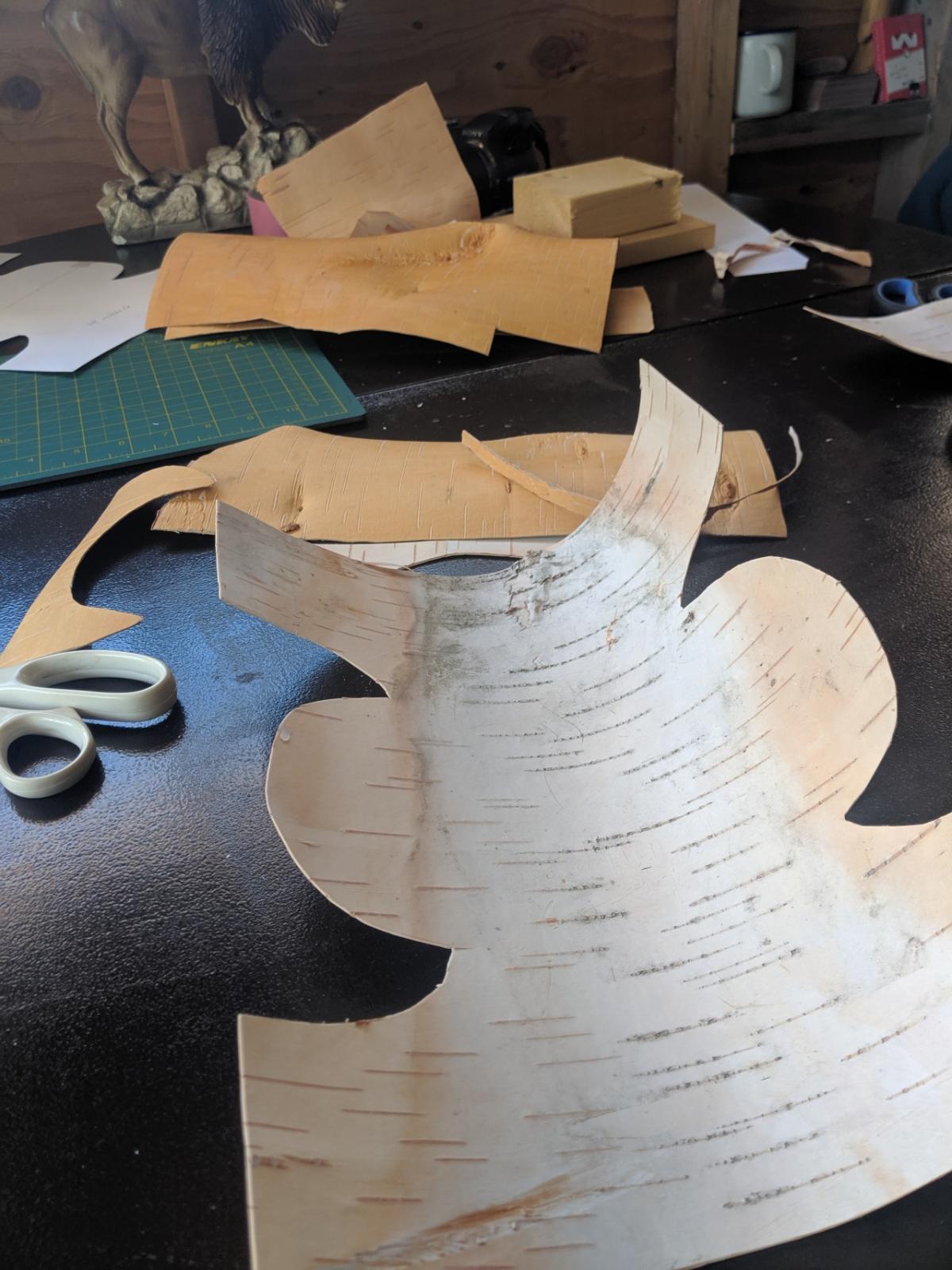

Once you have a pattern drawn and cut out, it can be traced with pencil onto the bark or scored with a penknife.

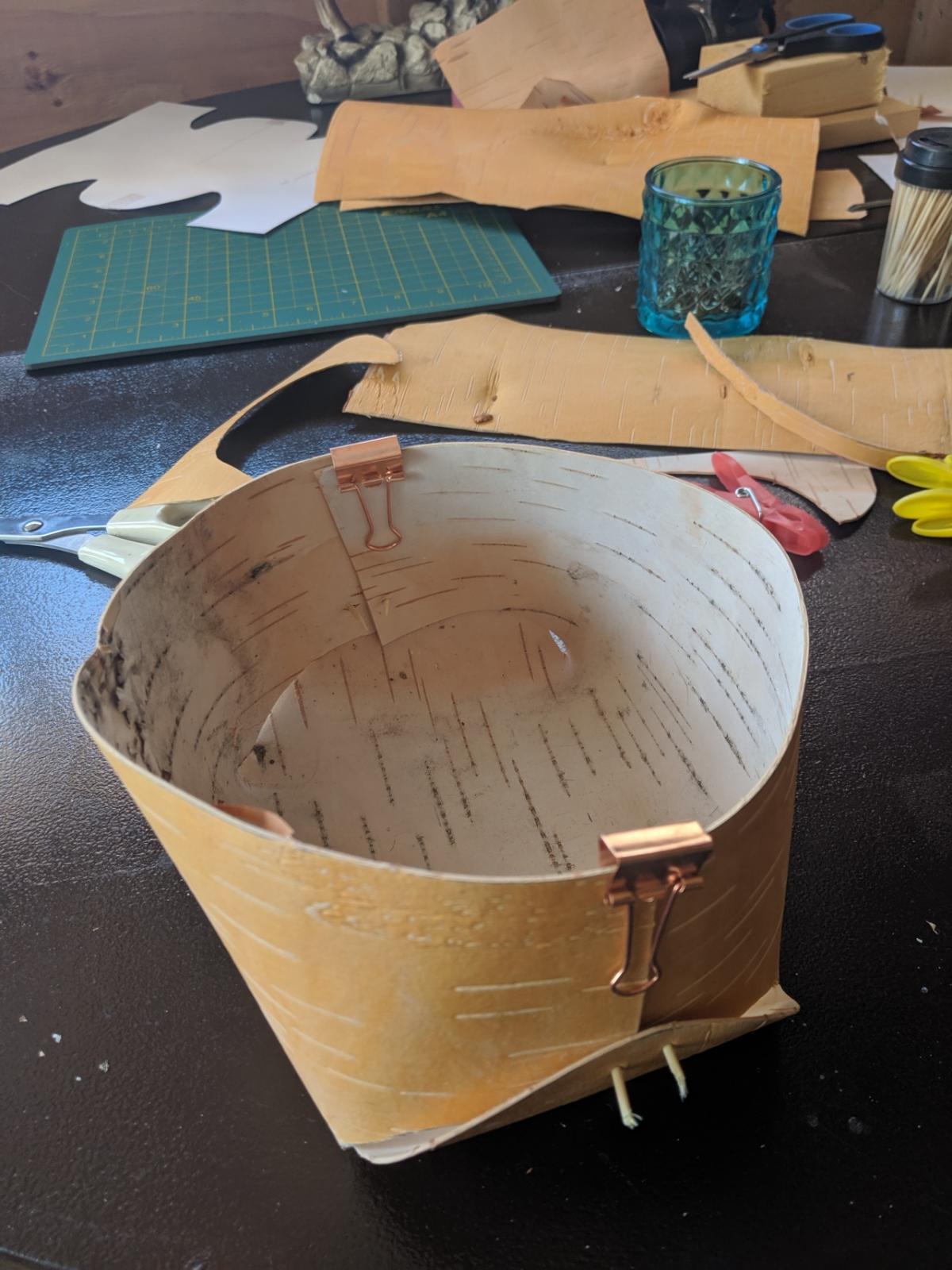

Cutting out the pattern is easy enough, but you want to work with the natural curl of the bark. Utilizing the bark’s natural tendency to curl opposite of its original shape by making the papery exterior the interior of the basket lends additional support to the basket’s structure. The sides can be easily folded and held together by paper clamps while you stitch it together.

Sometimes the bark is thin enough to puncture with a needle, but it’s best to use a dowel to poke the holes and plan how you want the stitching to go. A decorative trim can be made from the scrap of the bark. It adds strength to the basket’s structure and can be attached using either the same stitch or something different.

And here we have the finished products!

My mom also took a moment to make my knife a sheath from two long strips of bark woven together. She also took the time to make a conical tool called a moose-caller out of the remaining birch bark for her nîcimos (sweetheart).

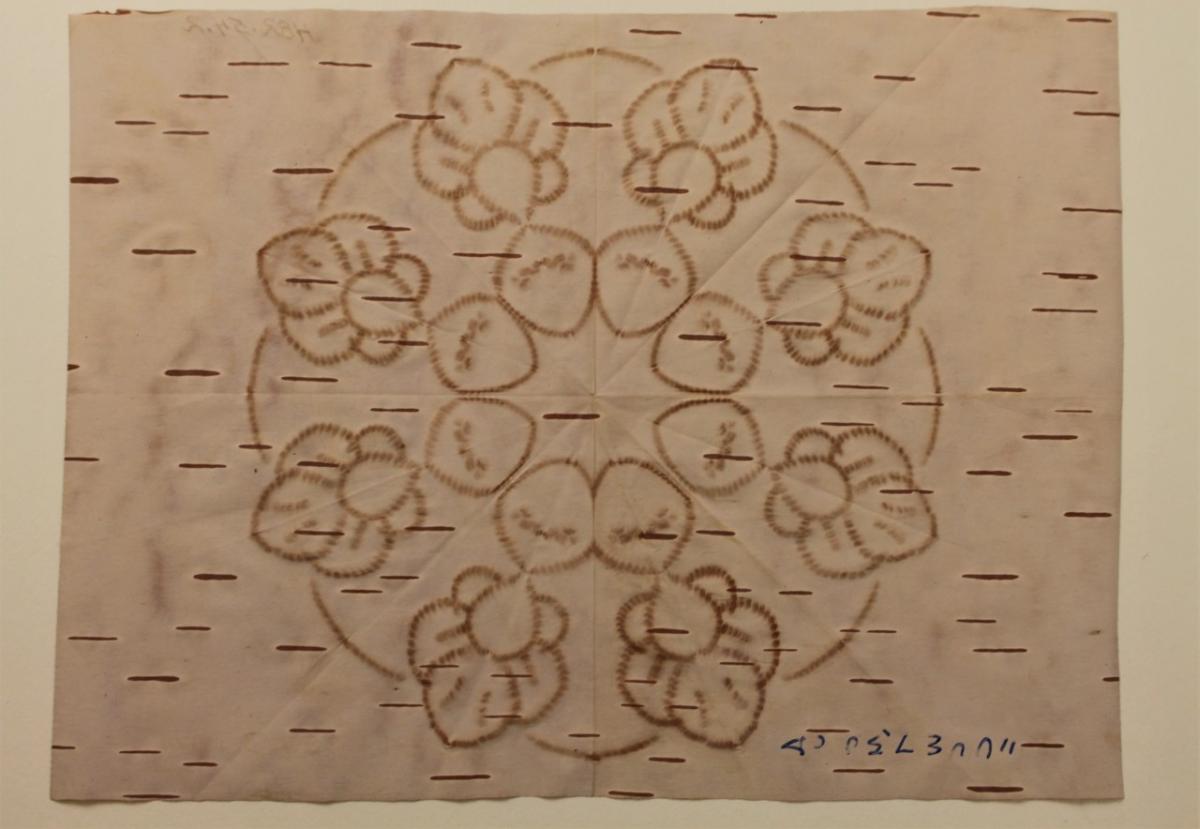

Birch bark biting is another art that utilizes the unique qualities of the bark. Stripped into thinner layers, the bark becomes paper that can be used for both artwork and for transferring patterns. Birch-bark biting was traditionally done by women and served as a kind of friendly competition between them. The individual would bite her pattern into the bark using her incisors and picture the design in her mind. Holding up the bark to the light would reveal if the pattern had transferred all the way through. Once satisfied with the design, it could be transferred onto any item they intended to do bead or quillwork on.

This was done by laying the bitten pattern over the item and using a thin layer of ash or chalk to transfer the image. The ash or chalk would fall through the holes in the bark and recreate the pattern on the other side.

With the availability of pencils, paper, and other materials the practice of birch bark biting is not used as frequently but there are still practitioners that produce beautiful pieces of artwork such as Halfmoon Woman (Pat Bruderer). The biting, of course, takes many hours of practice and as Angelique Merasty once said, it takes “wasting a lot of birch bark” to develop the art.

These objects showcase a union of utility and art that is characteristic of many Indigenous creations. Yet they are more than that. Through these we transform the material of the birch bark into a carrier of not just berries or buttons but traditional knowledge to be passed from generation to generation. In this way, waskway is not merely a resource but grandmother tree embodied.

Missed part 1? Read it here: Barking Up the Right Tree (Part 1) by Skye Haggerty